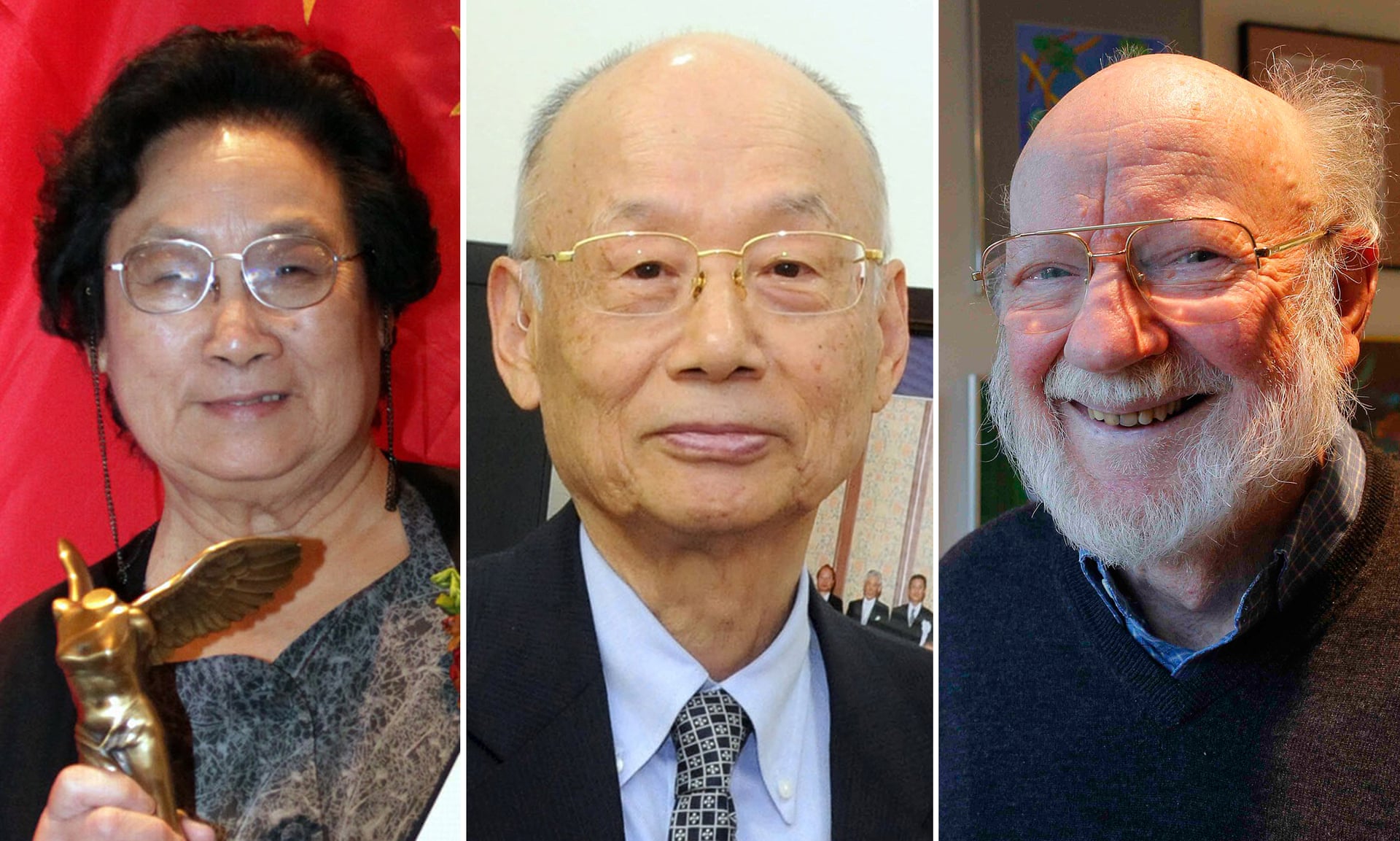

The 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine goes jointly to William C. Campbell and Satoshi Ōmura

Three scientists from Ireland, Japan and China have won the Nobel prize in medicine for discoveries that helped doctors fight malaria and infections caused by roundworm parasites.

Tu Youyou discovered one of the most effective treatments for malaria while working on a secret military project during China’s Cultural Revolution.

The 84-year-old pharmacologist was awarded half of the prestigious 8m Swedish kronor (£631,000) prize for her discovery of artemisinin, a drug that proved to be an improvement on chloroquine, which had become far less effective as the malaria parasites developed resistance.

Two other researchers, 80-year-old Satoshi Ōmura, an expert in soil microbes at Kitasato University, and William Campbell, an Irish-born parasitologist at Drew University in New Jersey, share the other half of the prize, for the discovery of avermectin, a treatment for roundworm parasites.

Together, the scientists have transformed the lives of millions of people in the developing world, where parasitic diseases that cause illness and death are most rife.

“The two discoveries have provided humankind with powerful new means to combat these debilitating diseases that affect hundreds of millions of people annually,” the Nobel committee said. “The consequences in terms of improved human health and reduced suffering are immeasurable.”

Based in Beijing, Tu was assigned to “project 523” by Mao Zedong in 1967 to find an effective treatment for malaria, a devastating disease that claimed more lives among the North Vietnamese troops in Vietnam than the US military. To observe the disease first hand, she was sent to Hainan province, an island off the southern coast of China, and had to leave her four-year-old daughter in the care of a Beijing nursery.

On her return, Tu and her team trawled through more than 2,000 Chinese remedies for clues on how to fight malaria. One recipe, written 1,600 years ago and entitled “Emergency Prescriptions Kept Up One’s Sleeve” proved crucial. It described how sweet wormwood, or Artemisia annua, should be prepared in water to treat the disease.

The first preparations worked at times, but not at others. Tu traced the problem back to boiling, which destroyed the active ingredient. She went on to make extracts at lower temperatures. In tests on monkeys and mice, these were 100% effective.

The first tests in humans took place in 1972 in Hainan when 21 people with malaria were given Tu’s preparations. About half had the deadliest form of malaria, caused by the parasite Plasmodium falciparum, with the rest infected with the most common cause, Plasmodium vivax. The treatments wiped out the parasites in both.

While Tu led the group at what was then the Chinese Academy of Traditional Medicine, and went so far as to drink her preparations to test their toxicity, other Chinese scientists played major roles in the development of artemisinin, notably Li Guoqiao, the clinical trials leader, and a chemist called Li Yin.

Ōmura and Campbell were cited for their discovery of avermectin. Derivatives of the drug have dramatically reduced cases of river blindness and lymphatic filariasis, and are starting to show promise against other diseases caused by parasitic worms. Lymphatic filariasis affects more than 100 million people.

Those who contract the disease can suffer swelling, including elephantiasis, and disability, that can lead to them being shunned by their communities.

Like Tu, the Japanese microbiologist Ōmura made his breakthrough by studying natural products. He gathered soil samples and from them grew bacteria that produced their own anti-microbial compounds. Among the strains he isolated was Streptomyces avermitilis from the boundary of the local golf course, which appeared particularly effective.

His work was taken up by William Campbell in the US, who found that Streptomyces avermitilis was remarkably effective against parasites in domestic and farm animals. The killer compound, avermectin, was modified into a new, more potent drug called ivermectin. In tests on humans, it wiped out parasitic infections, leading to a new class of drugs against parasitic worms.

Campbell was woken by a call from a reporter and did not believe the news until he checked on the Nobel website. He stressed he was one of a larger team at Merck in the US that developed ivermectin. In 1987, the company declared it would give the drug away free of charge for as long as it was needed.

He urged scientists to look to go back to nature in their search for drugs. “One of the big mistakes we’ve made all along is that there is a certain amount of hubris is human thinking that we can create molecules as well as nature can,” he said.

Ōmura said he was surprised and felt lucky to have won the prize. “It’s a very happy day,” he said.

Steve Ward, the deputy director of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, praised the winners for their exceptional discoveries. “Both of these compounds are central to current programmes to eradicate disease from the whole planet,” he said.

“Elephantiasis and river blindness blight the lives of millions of the poorest people on the planet, and ivermectin is having a genuine effect on reducing the burden of disease to the point that we can think about getting rid of them for good,” he said.

“Artemisinin was discovered when fatalities from malaria were rocketing and the world was terrified we’d be looking at a post-chloroquine era. It has been a real game-changer,” he said.

The medicine award was the first Nobel prize to be announced. The winners of the physics, chemistry and peace prizes are to be announced later this week. The economics prize will be announced on Monday 12 October. No date has been set yet for the literature prize, but it is expected to be announced on Thursday 8 October.

(TheGuardian)